Lee Walton:

If you had to sum up this action in one instructional sentence or formula it would be something like:

Use your hands to feel a diverse range of things in the city.

Notice he takes the common expression “Getting a Feel for Things” literally in this work, and feels things. See how he uses common expressions, and simple instructions as a formula for creating in the following videos.

If conceptually informed artworks are ones in which an idea determines the work, as opposed to the artist’s masterful technique, or the perfect handling of materials. In fact, when you follow directions, things might even turn out badly, things can break down, fail, fall apart. There is tremendous tension in this – when we really don’t know how things are going to go. Watch Jon Sasaki play with attempting to do something, and the possibility (and sometimes the reality) of failing, falling, or otherwise destroying everything.

Kelly Mark:

Sniff:

https://kellymark.com/V_Sniff1Video.html

Hello/Goodbye:

https://kellymark.com/V_HelloGoodbyeVIDEO.html

I love Love Songs but Angry Music Makes me Happy:

https://kellymark.com/V_ILoveLoveSongsVIDEO.html

Jon Sasaki:

Ladder Climb:

http://www.jonsasaki.com/index.php/work/ladder-climb/

Dead End, Eastern Market, Detroit:

http://www.jonsasaki.com/index.php/work/dead-end-eastern-market-detroit/

Harrison and Wood

Michelle Pearson Clarke:

Lenka Clayton:

Human Beings. 1-100 (2006)

“This is first in a series of four films – People In Order – commissioned by the UK’s Channel 4 in 2006. The concept behind our films was simple: we asked ourselves if you can reveal something about life by simply arranging people according to scales. Three minutes is a very short time to communicate something – perhaps too short to tell a story, or to get to know a character – so we wanted to make this series by setting ourselves some very straightforward rules, and then following them through over a long trip. The rules had to be simple so it would take the audience virtually no time to understand them. We established what scales we’d look at, and then chose how each film would be framed. Then it was a case of getting in a campervan and driving round Britain, filming as many people as we could over 4 weeks in February, coping with microphones crackling and our camera refusing to work.

The experience was exhausting but also life affirming. In our whole trip we were struck by how happy people were to help. Only a handful of our shoots were arranged in advance. We relied instead on the kindness of strangers – and we found that everywhere, from deprived urban estates to rural aristocrats.

The resulting films are like a list of government statistics where the citizens they are referring to have broken out from behind the figures on the page. The people on the screen stop us from seeing them as numbers.

Adad Hannah:

Blackwater Ophelia:

https://adadhannah.com/2013-blackwater-ophelia

The Russians:

https://adadhannah.com/2011-the-russians-videos

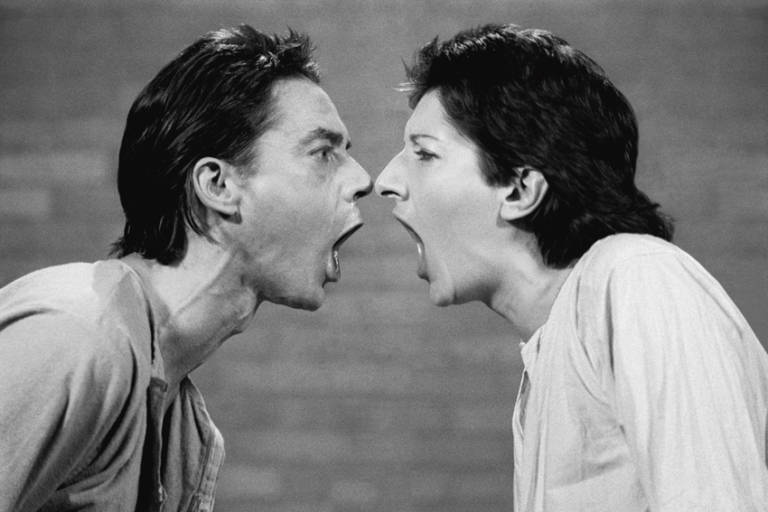

arina; Ulay, «Rest Energy», 1980

Standing across from one another in slated position. Looking each other in the eye. I hold a bow and Ulay holds the string with the arrow pointing directly to my heart. Microphones attached to both hearts recording the increasing number of heart beats.

Rineke Dijkstra

Candice Breitz

Candice Breitz

‘Legend (A Portrait of Bob Marley),’ 2005

Breitz’s experiments in the field of portraiture can cumulatively be described as an ongoing anthropology of the fan.

In each case, Breitz first sets out to identify ardent fans of the musical icon to be portrayed, by placing ads in newspapers, magazines and fanzines, as well as on the Internet. Those who respond to this initial call (typically numbering in their hundreds) are then put through a rigorous set of procedures designed to exclude less than authentic fans of the celebrity in question, in order to arrive at the final group of participants.

The individuals who appear in these works have thus stepped forward to identify themselves as fans, and have been included purely on this basis: all other factors – their appearance; their ability to sing, act or dance; their gender and age – are treated as irrelevant for the purpose of selection. Each of the selected fans is offered the opportunity to re-perform a complete album, from the first song to the last, in a professional recording studio. The portraits evoke their mainstream entertainment counterparts (such as American Idol or Pop Idol), but also take significant distance from their reality television cousins: Breitz promises her subjects neither fame nor fortune. What she offers them is an opportunity to record the songs that have come to soundtrack their lives in whatever way they choose. The non-hierarchical grids that she uses to organize the final presentation of the fans in each portrait, allow Breitz to deliberately sidestep the question of who has fared better or worse under the conditions that she has created for these quasi-anthropological visual essays on the culture of the fan. Whether the fans who pay tribute to their icons in her portraits are victims of a coercive culture industry or users of a culture that they creatively absorb and translate according to their needs, is left to the viewer to decide. If the dignity of the portrayed fans remains surprisingly intact, it is because rather than prompting us to laugh at the fans that she lines up, Breitz forces us to reflect on the extent to which pop music has infiltrated our own biographies.

Titling the series of works as she does, Breitz asks that we locate these multi-channel installations within the genre of portraiture, and prompts the question of how they in fact relate to this most humanist of genres. (From the artist’s video channel)

You must be logged in to post a comment.